In 1968, my first year as a Morocco X Peace Corps volunteer, I and the other volunteers in this program worked as agricultural extension agents assigned to Moroccan government farming centers, in my case near the town of Sidi Kacem. Towards the end of this first year, the PC volunteers in this agriculture-focused program were widely dissatisfied. Generally the program and our assignments were not working. With participation by the Morocco Peace Corps director, the volunteers met and successfully insisted that the program be terminated with volunteers free either to stay at their current assignment or transfer to another job somewhere in the country. Thus in my second year of Peace Corps service, I ended up in the capital city, Rabat, teaching English to university students in a modest program which I really enjoyed.

For the first time, people were no longer puzzled by my presence. Suddenly my being in Morocco made sense, both to them and to me. I loved Rabat, an absolutely beautiful city. I walked or bicycled its streets daily. Though fellow volunteers and a few British adventurers were my steady friends, two quite different Moroccans also became friends.

One was a high school student who invited me more than once to his home and who had long conversations with me in Arabic. I wrote back home to my father’s Rotary club in Montana asking for the club to make a donation to help this student go on to the university. I got no response. I ended up making a secret donation of my own which I pretended was from the club.

The other Moroccan friend was originally from the Sous, a dry, poorer southern region of Morocco. When I met him, he was working in his father’s café located near the entrance to Rabat’s medina, the part of the city that existed before the French arrived and built their adjoining French quarter.

Mohammed could always be found sitting behind the cash register at the entrance to the café. He had become friends with some of my British friends and had taught himself English, being more accomplished in English than French, which was astounding, because French was the default second language in Morocco.

Mohammed eventually led me to understand that in some ways he felt imprisoned by the patriarchal culture of his family. For example, he could not marry until his older brother married, and his role in his family’s business was mandatory. ln addition I also began to wonder whether, coming as he did from a poorer region of the country, he also felt a little alienated from the Rabat city culture. So in searching for his way forward, he had not only cultivated friendships with Brits and Americans, but also eventually (after my Peace Corps tour was over) moved to London and found himself totally overwhelmed by the enormity and impersonal nature of that world metropolis. He lasted there for six months and when he returned to Morocco and got off the plane, he kissed the ground, so grateful to be back.

I know this because nine years after the end of my 1968-1970 Peace Corps tour, my wife and I visited Morocco and we looked Mohammed up. We found him still sitting behind that damn cash register. He was happy to see us and arranged to meet after work, and over the course of the next several days, we had extended visits. He gave me considerable insight into his own situation as well as commentary on Morocco seen from within the tensions of his own perspective.

He started out by telling me I had changed his life. How, I asked, astonished. He said I had left him my Peace Corps book locker and he had read a lot of the books, including books on philosophy. He said this reading, plus his time in England, had helped him understand the Western idea of individualism—an idea alien to his own family and upbringing and to some extent to the Morocco he knew. He had later returned to London a second time for a more extended stay but did again eventually return home to Rabat. He explained that he was not going to introduce my wife and me to his family because the tension between his relationship to his family and his relationship to us made him too uncomfortable.

He also commented that there were people in Rabat today (in 1979) who thought the Tour Hassan, an enormous abandoned mosque tower, was so high that it could only have been built by jnun, the powerful invisible sprites that a great many Moroccans believed in.

He also said that gleaming Europe, a stone’s throw away on the other side of the Mediterranean, seemed to many Moroccans (at least in his estimation) not merely a more advanced civilization but a different planet inhabited by a different species with superhuman powers.

Morocco harbors a very wide variation in its population, ranging from cosmopolitan people who often speak French rather than Arabic at home, to peasant farmers who, at least in my day, were still living with an almost medieval understanding of the world. I don’t present my friend Mohammed’s comments as an accurate or even fair portrayal of a complex and very interesting country. I do think, however, that they show the uncomfortable tension that he carried, as a Moroccan, between the patriarchal culture of his upbringing and the individualistic culture of the West. I would guess these tensions are widespread and shed at least indirect light on the clash in recent decades between the Arab world and the West.

Like most former volunteers, I remember my years in the Peace Corps and the country in which I served with gratitude and affection.

Living in Morocco changed my life for the better. I came to realize how very different cultures in other parts of the world could be, that the standards of my American culture were not bindingly final, and how irredeemably American I was.

Jim Humphrey

1968-1970 Peace Corps, Morocco X program

Thank you for sharing that account, which was fascinating and beautifully written! Who took the fabulous photos? Kinza

Virus-free. http://www.avg.com

On Tue, Nov 17, 2020 at 11:04 AM Morocco That Was wrote:

> Dave posted: ” In Rabat, with my bike. In 1968, my first > year as a Morocco X Peace Corps volunteer, I and the other volunteers in > this program worked as agricultural extension agents assigned to Moroccan > government farming centers, in my case near the” >

LikeLike

Thank you Kinza. The picture of Jim with the bike is one of Gaylord’s. The others are mine. Any chance of a piece about your experience? I think that it would be memorable and a perfect fit for this blog. Your experience was extraordinary.

LikeLike

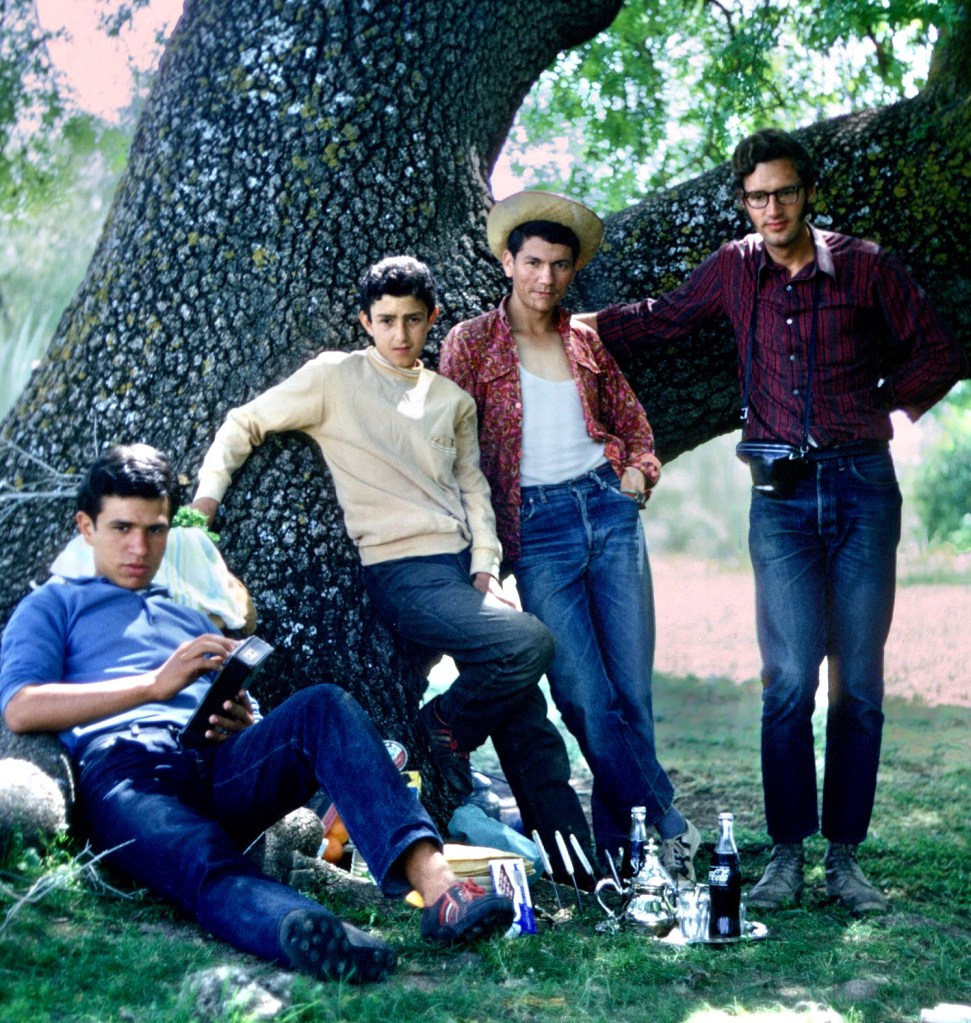

Jim’s clear eyed account of his Peace Corps service in Morocco is moving in its sincerity and simplicity. The accompanying pictures bring back a lush, colorful and youthful world a half century gone by. That Morocco has largely escaped the awful travails of its Maghrebin neighbors is a tribute to the tolerance, grace and intelligence of the Moroccan people, and the spirit of friendship and humanity that Jim and, by extension, the entire Peace Corps enterprise has brought to Morocco for more than six decades… and yes, I agree that Kinza’s story would be a great addition to the “Morocco That Was”.

LikeLike

Great photos, as is the case with this blog! It all helps me reminisce on what a fabulous adventure it was for me to spend almost 5 years in Morocco.

LikeLike

Thanks, Sam. Have you notice you are in at least one of the Hemet photos?

LikeLike

Fabulous post. You really take us in to the culture here. Just what I like!

LikeLike