An old classmate from Dartmouth College wrote me this year asking if I would like to contribute to a compilation of articles about the service that the Class of ‘67, my class, made to the Peace Corps. My submission is printed below. The contribution of my classmate and friend Jim Humphrey has already been published on this blog in a previous post Dartmouth in Morocco.

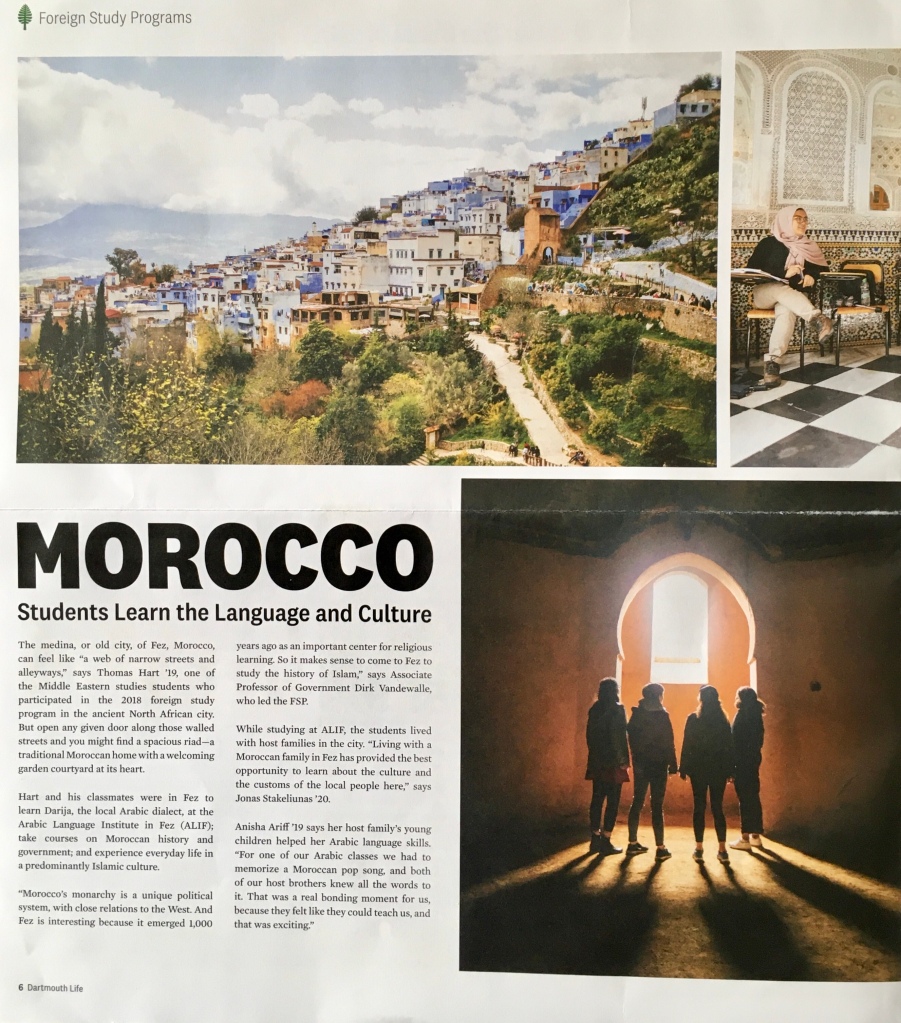

Fifty years ago, there were few academic courses at Dartmouth that focused on Islam, let alone on the newly independent Islamic country of Morocco. Foreign language programs focused narrowly on a few European languages, and very narrowly at that. When I asked, as a student, about a course in French Canadian literature, a member of the French department replied sarcastically, “Is there any?” Today, according to Dartmouth Life (Fall 2018), Dartmouth not only provides students with a foreign living experience in Fes, Morocco, but one that includes learning the local Arabic dialect, which Moroccans refer to as darija. These students will not live there long enough to experience earthquakes, repeated winter floods and landslides, or attempted coups, nor will they probably perceive Morocco as the majority of Moroccans do: a never ending struggle to obtain enough money to survive. Still, the initiative is a welcome one, and to be applauded.

My Peace Corps service and my own exposure to Morocco owes multiple debts to my alma mater. Not only did Dartmouth provide me with two valuable foreign living experiences, one in France and the other in French Canada, the College also introduced me to a friend who encouraged me to go to Morocco. He swore that I would love his country. He was right.

Dartmouth’s semester abroad, offered through The Experiment in International Living, provided my first opportunity for a long stay outside the United States. Though I graduated from Exeter, I had lived in poverty as a youth and there was no foreign travel in my life before Dartmouth.

Dartmouth, with its language requirement, forced me to get serious about learning a second language. I first began Spanish in high school and then added French and Russian. Arriving at Dartmouth in the autumn of 1963 with no decent command of any of the languages that I had studied, I chose to continue with French. Today I credit Dartmouth with my lifelong love of French, in particular, and of foreign languages in general, though I can’t honestly say that the undergraduate instructors, junior faculty members, and visitors were particularly inspiring. My excitement came from Racine and Balzac and the traditional corpus of French literature, and, like most literature that I was forced to read in my youth, I have come to love it much later, after multiple readings and more cultural context.

In the fall of 1964, I needed a job to make ends meet, and found one involving work at the Reserve Desk in Baker Library. I suppose I can give Dartmouth a bit of credit for my interest in libraries, too, as I ended my working life as a librarian.

With modern technology, reserve desks have been replaced by online services, but in the mid-nineteen sixties, photocopying was in its infancy and expensive. The reserve desk loaned assigned readings for use in Baker, and most students used them in the basement, surrounded by the remarkable murals of the Mexican revolutionary artist, Orozco.

I worked nights, and often weekends. The Reserve Desk was seldom busy except near exam time. A perk of the job was that my supervisor would sometimes let me leave early on Saturday nights when there was little demand, and she could handle the closing hour alone.

One my coworkers was Loretta Comstock. Loretta and her husband, Kurt, a student, were returned volunteers who had served in the first Peace Corps program in Morocco.

I babysat for them, and remember seeing a picture in their apartment of one of the monumental gates of the city of Meknes. I knew nothing about Morocco at the time, and do not remember talking with them much about their service or Morocco. What I do remember was Loretta complaining bitterly about facing discrimination while growing up Hispanic in Colorado. I still consider my introduction at the College to the civil rights struggle, discrimination, and prejudice as important as anything else I learned there.

Dartmouth in France: Montpellier

In 1965, when I went to France for six months, the important news of the autumn for us students was the escalation of the war in Vietnam, the huge power failure in the U.S. Northeast, and the Dartmouth football team’s perfect season.

The French news, on the other hand, prominently featured stories about Mehdi Ben Barka, Morocco’s most significant opposition leader, who had been abducted in Paris with the complicity of French police, then tortured and killed. This violation of French sovereignty enraged then President De Gaulle and soured Franco-Moroccan relations for a time, but it barely registered with me. L’affaire Ben Barka was truly off my radar.

Cutter-North Dorms

Returning to campus in early 1966, I took up residence in North Hall, and then moved to Cutter in the spring of my senior year. The Cutter-North complex was intended for international students and American students who had an interest in foreign affairs. My dorm room in Cutter was across the hall from that of a Moroccan, Badreddine Bennani, Class of ‘68, whom everyone called Ben.

There were returned Peace Corps volunteers in the Cutter-North complex, and, as I began to think of taking a break from future study (as well as looking for a deferment from the war in Southeast Asia), I became friends with Ben who pushed me to go to Morocco. My friends were also considering the Peace Corps. Bob Wood ‘67 went to Thailand, and Jim Humphrey ‘67 ended up in my Morocco X program. I have since learned, that at least a half-dozen volunteers from the Class of 1967 lived in Cutter-North.

Peace Corps at Dartmouth

Before graduation, the campus Peace Corps office, run by Phil Boserman, was hiring for summer training programs in Quebec.

The previous fall I had studied at the French-speaking Université de Montréal and I had written my senior honors thesis on La révolution tranquille in Quebec. With a better than average knowledge of French Canada, I was hired as a program assistant before graduation. In the spring of 1967 I was sent to Quebec City to explore potential training sites. Bob Wood came along.

Ste-Anne-de-la-Pocatière

In the end, the next summer training site turned out to be at a Catholic collège in La Pocatière, about 80 miles downstream from Quebec City, in a small village on the banks of the St. Lawrence. I worked in programs training volunteers for Senegal and Cameroon.

Training

I applied for the Peace Corps at Dartmouth, and while at La Pocatière, I received an invitation to train for a program in Senegal. I wanted to be sent to Morocco, so I declined, thanking the Peace Corps for the invitation, and restating my interest in Morocco. Late in the summer, I learned that I had been accepted to train for an agricultural program, Morocco X. Dartmouth friend, Jim Humphrey wrote saying he had been accepted, too, and was excited. I was, too.

Morocco X trained in Hemet, California, a sleepy town in an inland valley near Riverside. The idea behind the program was providing extension agents who would work with the Moroccan Ministry of Agriculture and farmers to introduce new varieties of wheat.

Before the two-year program was half over, however, most of the volunteers who had not already returned home early, were working in different fields ranging from fisheries to teaching English as a second language. The ambitious program was a disaster despite great training and hardworking administrative staffs.

Peace Corps Morocco had few really successful programs in its first decade. It was unrealistic to think that volunteers without an agricultural background could become extension agents overnight, all the more so since the Moroccan Ministry of Agriculture not only lacked the means to use the volunteers effectively, but was structured in such a way that made agricultural extension as Americans know it difficult if not impossible.

Newly independent Morocco was still mired in political conflicts of colonial origin and managed by a French-educated elite feeling its way, and looking after its own. The early days of Peace Corps administration were endowed with a surfeit of enthusiasm and idealism, but often flawed by a serious deficit of realism and a host country still learning to self-govern.

Sefrou and Fes

I quickly moved from my post in a rural agricultural center outside Meknes to a primary school cooperative in Sefrou. When the director of the school died, the cooperative no longer had its sponsor and folded. I found a new job doing audiovisual extension work for the Ministry of Agriculture in Fes, and worked there for two years.

The poultry cooperative was in Sefrou, a small city on the edge of the Middle Atlas Mountains, about 20 miles from Fes. Despite changing jobs, I continued to live in Sefrou, commuting to Fes by shared. taxi and bus.

My work life in Fes, which involved other foreign nationals, was quite separate from my home life.

A few years later, returning to Fes, I bumped into my former colleague, Mr. Mernissi, whom I had trained in photography, and I was pleased to learn that he was continuing the work that I had started.

Who are the people in my neighborhood, the people that I meet each day?

In Sefrou, I only associated with Moroccans, largely teachers, students, and the shopkeepers around my home in the medina, the old walled city.

Life in Sefrou

Sefrou was an old Arab-Jewish city, but changing rapidly with an influx of Berber-speaking country people and a final exodus of local Jews and colonial French. While I was there, the Catholic church closed and was sold.

The colonial French were packing up, to be replaced by young French doing their national service. One missionary, two or three Peace Corps volunteers, a series of American anthropology students directed by the eminent scholar, Clifford Geertz, and some odd European expatriates, rounded out the foreign population.

Sefrou occupies a shallow valley on the limestone edge of Middle Atlas plateaus that gradually rise from three to six thousand feet. The paved road that passed through the city connected Fes, an imperial capital, with the heartland of the ruling dynasty south of the High Atlas Mountains on the edge of the Sahara. The route was known traditionally as the treq-es-sultan, the Sultan’s way.

In 1968 the city consisted of a quiet and spacious new town of villas on the hill, built by the French in this century during the protectoratea, and a noisy, bustling old walled city, cut by a river, below it.

My house, just inside a city gate, was only a few minutes walk from countryside, and locals often would spend good weather days picnicking in the orchards and cemeteries surrounding the city, walking, eating and drinking tea while taking in the fresh air and sun, or, in the case of students, studying.

Within the old city was a mellah, or Jewish Quarter, and one of the traditional sights had been Jewish women washing clothes alongside it. When I arrived, newer quarters were growing up around the old city, but its gardens and orchards, famous for cherries, still stretched beyond the built-up areas.

Change as it happened

As Morocco’s population grew rapidly, the economy did not keep pace, and wage labor migration to Europe, which had begun in the early 20th century, increased rapidly. At first characterized by its temporary nature, men left their families behind in Morocco, a traditional form of migration in North Africa. As time went on, however, more and more families emigrated. Moroccan Arabs, like Moroccan Jews, were forsaking the land of their ancestors for new lives around the world.

Until the Peace Corps arrived, few Moroccans had much contact with Americans. The Cold War SAC bases, near Casablanca, were gone. Only a couple of small U.S. Navy bases remained. There were consulates in the largest cities, a USAID mission, USIA libraries, again only in a few large cities, and a couple of schools for American dependents. American tourists were everywhere in major centers, of course, the wealthy seeking the exotic, and the young looking for adventure. The fact that Tangiers was a quick ferry trip from Spain made a visit to Africa a convenient addition to any European vacation or tour.

In smaller places, such as Sefrou, Americans were rare. Moroccans were quite interested in who we were, though it was not always clear why we were there. Volunteerism was not characteristic of family-oriented Moroccan life, where most people struggled just to make their way. Many Moroccans categorized us as trainees or spies.

Since many early programs in Morocco were unsuccessful, the Peace Corps’ first goal, to provide valuable manpower to developing countries often went unmet, though not for lack,of trying. The second and third goals, fostering cross-cultural understanding, succeeded brilliantly. For a young American, what could provide a better knowledge of a foreign country than living a life among its people, a level of society far below the upper class. For Moroccans, in turn, volunteers provided flesh and blood representatives of a country they all had heard of, but scarcely knew.

The volunteers in my group learned dialectical Arabic, which facilitated interaction on a personal level. Other foreigners, such as the French and Spanish, could get by in their native tongues, both former colonial languages in Morocco. Moroccans were surprised, and, many I think, honored by our knowledge of their dialect, though some wondered why volunteers who were supposedly educated did not know French or Modern Standard Arabic, the written dialect.

The “Posh” Corps

I have heard volunteers from other countries describe service in Morocco as the “posh” corps. Living there certainly did not have the isolation and deprivations of some Peace Corps assignments.

I saw this firsthand traveling to many West African countries after hitching across the Sahara in the spring of 1971. Volunteers south of the Sahara often had to travel hundreds of miles over bumpy dirt roads just to get anywhere!

Sefrou was a great place.On the other hand, life in smaller more isolated Moroccan towns and hamlets wasn’t easy at all, especially for women volunteers.

I suppose that posh is how you look at it. I shared a traditional house with another volunteer and had a housekeeper who made bread daily, cooked one meal a day, did laundry, and kept the house spotless. She also provided a window into the world of women, and a source of information, advice, and important superstitions.

The masonry house had no heat, no hot water, no true kitchen, and no shower. Posh? Not at an elevation of over 3,000 feet where the cold settled in for months in the darkest days of the year and the damp caused my bamboo shelves to mildew. Moroccan personal warmth, traditional hospitality and lifestyle made those tribulations bearable.

No shower? Every city neighborhood had a hammam, a public bath, in which one got squeaky clean, could socialize with friends, and acquired a warmth that lasted long after emerging into the cold winter night.

Morocco was well furnished with roads. Like the Romans, the French built roads for conquest and commerce. Dick Holbrook, one of the country directors and a refugee from the State Department at that time, once confided to me that one of his ambitions was to drive every paved road in the country. I doubt that he ever succeeded, but most volunteers, who usually had no vehicles, could reach a major city in a few hours, and almost no one was farther than a day’s travel from Rabat, site of the Peace Corps office.

Still, many volunteers were isolated. Telephones were rare, TVs scarce, radio emissions limited, and, unless one read French, newspapers were published in an unreadable foreign language since standard written Arabic differs greatly from the Moroccan dialect. Furthermore, as non-Muslims, volunteers were excluded from participation in religious events which,were far more important than in our secular society. In the quiet nights, listening to shortwave broadcasts, I came to love the BBC World Service, and relied on it for both entertainment and news of the world. The program Desert Island Disks still has a special meaning in my life.

Visitors

Close to the U.S. and Europe, Morocco had frequent official and semi-official visitors. One U.S. senator on a junket stumbled off his plane in Tangier quite drunk, and declared how happy he was to be in Tunisia. David Rockefeller, who had a long and personal involvement in Morocco and who made many trips there, once declared to his hosts that he was tired of official government views. For a dinner in Fes, the local police literally pulled volunteers from the streets and cafés to attend a dinner for Rockefeller.

I myself was invited to a dinner with Lady Bird Johnson’s press secretary, Liz Carpenter in Fes. In return, I hosted her and her daughter at my home in Sefrou where she was able to watch couscous made from scratch and eat a true Moroccan meal.

Carpenter was a genuine Texan, warm, down-to-earth, and tough, not at all bothered by a house with no sit-down toilet. Her visit was fun.

Dartmouth visited me once as a volunteer. In Fes, I had missed a bus that had my checked baggage, including my passport, stowed away. I was on my way to Kenitra, for a medical evacuation flight to the then U.S. Air Force airbase at Torrejón in Spain. Desperate, I tried to beat the bus to Rabat by hitchhiking; a white Peugeot 504 stopped and the driver, who spoke perfect French, offered a lift. To my great surprise—and delight—he was a U.S. military officer from the “secret” U.S. base at Sidi Slimane in the Gharb. He turned out to be Dartmouth Class of ‘68, and he got me to Rabat before the bus. To my great relief, I was able to retrieve my suitcase and passport.

The Goals of the Peace Corps

Did my service have long-lasting effects on the development of Morocco? To say yes would be presumptuous, if not outright mendacious. Just the same, two of the students I knew as friends ended up as university professors, an achievement that was made possible to some degree by not only being taught, but also by being befriended by Americans, and, in particular, the PCV English teacher at the local lycée with whom I shared the Sefrou house, Gaylord Barr. They succeeded and live happily in Morocco today, but most of the people who lived around me did not have the educational opportunities of those students, and emigrated to France seeking a better life.

Recently, one of those students wrote me asking about life in America today.

Hi Dave,

In case you didn’t get it! Check out this article about Sefrioui Jews published by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. I was really touched by it; it brought back many happy memories, especially your pictures of the gate of the Jewish cemetery, which, if you remember, is across the road from my house, and that of “Kef al-Moumen” (The Cave of the Believer). It’s so weird that while reading this excellent article about the peaceful coexistence and tolerance…that existed, I suddenly hear the breaking news on CNN about the El Paso and Dayton.

What’s happening to the America that I learned so many good things about from Gaylord, you, and other PCVs? What happened to the great American values and the ideals of John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan? Surely, something is rotten in Denmark! What is the difference between white supremacists and ISIS terrorists? In my younger days, my wish was to migrate to America, but now I say to myself ‘I’m glad my wish did not come true.’

Letter from old friend, Ali, last year. He did graduate work and graduated from SUNY Binghamton in the late eighties.

I have not been back to Morocco since the nineteen seventies. When I visited Ben Bennani at his family home in Tangiers in 1971, the city had a population of 275,000. Today it has over two million! And Ben, when I last checked, lived in Arizona. My Peace Corps service was over fifty years ago. Sometimes those days seem as far away as the pre-colonial times when Europeans nations vied for control of Africa. Still, sitting in my yard, watching freighters heading for the Atlantic, I occasionally wonder if one of them will stop in Morocco. When I reflect on my days in the Peace Corps, they often seem like yesterday. I have Dartmouth to thank for an experience that as a young adult, I could scarcely have imagined, and will never forget.

Very interesting! You must have a lot of good memories. I worked for the US Navy Bureau of Aeronautics in Washington DC and thought that was a big deal. Elaine Sdao😷😷 Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

I owe all my adventures in life to the teachers and educators who helped me along. Please tell that to Bill.

I would not dismiss your own experiences in Washington. I spent a summer in Georgetown and thought that Washington was fascinating.

LikeLike

Stay safe. Vaccines won’t be here for sometime. My grandmother Cortese had twins die during the 1918 pandemic.

LikeLike

Fascinating as always, thank you. Does the French in other countries differ greatly from the official Académie Française language? My only experience is in Belgium where it was pretty much the same but a few things tripped me up, for example ‘nonante’ rather than ‘quatre-vingt-dix’

( “The Reserve Desk was seldom busy except near exam time.” – ah, some things never change! )

LikeLike

That puts some of your earlier articles into context. Really enjoyed the adventure!

LikeLike

Thanks Dave, always fun to read. Great photos too.

LikeLike

Thanks, Sam. If it strikes your fancy, you could contribute a post or two—or several. I only wrote the last one because I was forced by circumstances, but I have a couple of more in the oven.

LikeLike

Wow, quite a saga, and beautifully illustrated. Your current memories and well informed choices at such a tender age are remarkable. When I bailed out of Cornell for “a leave of absence” after my sophomore year in 1965 to join the Peace Corps, I received the invitation to train for Morocco X, and initially confused it with Monaco, wondering if Princess Grace (Grace Kelly) would be in residence. Peace Corps Morocco was like going to the movies and stepping out of the audience, onto the screen, and into a new and, at the same time, ancient world. How lucky we were…and are, to have lived such a life.

LikeLike

What an interesting way of putting it, Reed. But as for the saga, I think you have a better claim than me. Maybe we should think of it all as an epic in which we were lucky to have bit parts.

LikeLike