When I began this blog, I used old color slides from the nineteen sixties as prompts for much of my commentary. I thought many of the photos that I took were interesting enough to share widely and some represented parts of my Peace Corps experience very well. Although I still have many slides from Morocco, I left off digitizing them a couple of years ago. Needing writing prompts, I have for some time looked to old documents, artifacts, and the media, but I haven’t posted nearly as often. Now, occasionally, an old memory or something that I wrote here earlier prompts me to write.

In the case of this post, I previously referenced the film Before Sunrise. The young protagonists of that film, French and American, meet on a train. The young man convinces the girl, who is on her way home to Paris, to stop off with him in Vienna where they spend the night walking and talking. He will fly home to the States in the morning, and she will resume her journey to France.

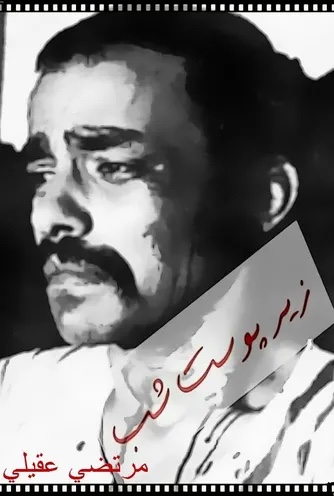

After I had written the post, another movie with a nighttime setting came to mind and made me think of Morocco. I watched the second film, Under the Skin of Night, (zir-e poost-e shab), in a theater in Tehran, Iran, in July 1974. Though my command of Farsi was poor, the dialogue was minimal and the action made most of the movie clear.

The theme of both films involves young people who meet by chance and decide to spend the night together. In Before Sunrise, the protagonists are privileged and wealthy enough to afford foreign travel, and self-discovery is not a luxury, just a part of growing up. They fall in love, even propose a future meeting in six months, to test the strength of their feelings. Their meanderings on a summer’s night in Vienna are filmed in color and involve no hardships.

Zir-e poost-e shab has a different story altogether, and begins, with a scarab beetle rolling a ball of dung. A young American tourist in Tehran spies a petty thief in the act stealing hubcaps, and her complicity creates a bond. The two do not search for meaning in life, neither speaks the other’s language, but, much more basically, for a place to have sex. For the girl, the sex will be casual. She, too, will catch a flight home in the morning. For the man, the night is the chance of his life to bed down with a foreigner, and perhaps even steal a new life from fate. But only one of this pair is privileged: the other lives from day to day on the edge of society.

Filmed in black and white, the story centers on a long, tiring, and ultimately fruitless search for a place where the two can be alone. He has no money. Living on the street, the man’s class and poverty work against his chances. Central Tehran is cold and unwelcoming. He takes the girl to Shemiran, a wealthy northern suburb that more closely resembled Beverly Hills than the rest of Tehran. The girl swims topless in the pool of a rich estate where his father was employed as a gardener, while the man is beaten up and thrown into the street. He ends the night in jail. There is no future to his relationship with the girl. They will never meet again.

I worked in Fes, a prime tourist destination, easily reached by bus or train from other major Moroccan centers. My office was in a government building in the Ville Nouvelle. As I lived twenty miles away in Sefrou and could not go home for lunch, I spent many hours in cafes, eating tuna-filled baguettes and nursing Cokes, often cut with a local sparkling water, Oulmès.

Young foreigners frequently visited Fes during the tourist season, and I often watched as equally young Moroccan hustlers worked to pick up tourists with offers promising authentic tours. Morocco was a place of unemployment and underemployment with a young and rapidly growing population. I once asked a shoemaker in Chauen if he’d ever been in the army. He replied laughing, “Yes, of course, in the army of the sitting”, a common reference in Arabic for the unemployed. Without family support or connections, neither an education nor a job came easily.

Tourists were easy marks, especially those without good French, and the medina, the old city, was a maze of winding streets and alleys, not at all easy to navigate, a place where a guide was useful. The would-be guide could sell his services, collect commissions from the shopkeepers selling tourists everything from cheap souvenirs to expensive rugs, and sometimes offer nighttime accomodation, with sex always a possibility for the older and most charming. Sex for most young Moroccan men in those days virtually always involved prostitutes. No other women were available.

As for the foreigner, sex with a native might make an exotic souvenir for some. The sixties in the developed world were a period of experimentation with drugs and sexual liberation. Young people traveled the world as if they were still at home, and, being far from the eyes of their families, had even fewer social constraints abroad.

Moroccan street people were happy to oblige them. However, Moroccans (and Mediterranean men in general) looked down on the sexual mores of young western women and many found it hard to distinguish the sexual freedom of foreigners from that of local prostitutes. In those days, young women were seldom available for young men except through prostitution. The freedom of western women was incomprehensible. I heard this opinion often in North Africa, and once even here in North America.

I remember a night in Montreal, when a college friend and myself arrived to pick up our dates, two nurses. They shared an apartment and when we arrived, there were two Lebanese guys about to leave. Unaware that my buddy had grown up in Beirut and spoke an Arabic dialect, they talked freely with each other, disdainfully referring to the two women as prostitutes. I think that they had dropped by thinking the women had no plans that night and were disappointed. When Steve, addressed them in fluent Lebanese Arabic, they were taken aback. For us, their comments took some luster off the dates.

Moroccan hustlers did not target resident foreigners who usually kept to their own social circles. Volunteers usually dated other volunteers, consular personnel, French coopérants, or had girlfriends back in the States. A few volunteers that I knew did visit (or were visited by) local prostitutes, especially in Middle Atlas towns or in big cities.

Volunteers and coopérants were a privileged group. Though watched by the police and neighborhood informants, they were almost never arrested or prosecuted, and occasional, perhaps even habitual, bad behavior was overlooked. They were short-term guests of the government.

I cringed a bit as I observed the hustlers at work. They preyed on the naive and those avid for “authentic” experiences. Years later, as I look back, I am a bit less judgmental about their behavior. The influx of country folk had already turned much of Fes’s medina into a slum. Morocco’s population was growing quickly and a large segment of the population was under 21. Young Moroccans earned their money as they could, found sex where they could, while privileged foreign youth pursued pleasure and excitement, sometimes with an insouciance that astounded me. Caveat emptor.

The final scene of Under the skin of night is both powerful, sad, and as symbolic as the Sisyphean task of the scarab. Escaping class and poverty, in societies where great inequalities exist, is nearly impossible for most. A young Moroccan’s best chances for a good life often lay abroad or depended on foreigners.

As a footnote, the movie, Under the skin of night, though well regarded, seems to be difficult to find, but there is a poor copy, with limited English subtitles, on YouTube.

Many thanks Dave.

2nd March 2024 will be the 50th Anniversary in Marrakech of the death of Rom Landau. Did you know him? The Polish & British Embassies in Rabat are organising some commemorative events. A museum in Berlin [who have discovered links with RL] are planning some lectures to be called âThe Rom Landau Lecturesâ.

Best wishes, David http://www.romlandau.org

LikeLike

It must have been fascinating to have been there during the blossoming sexual liberation of the 60s and 70s.

LikeLike