When our Peace Corps group trained in Hemet, California, we watched a black and white documentary film about Islam entitled, if my memory serves me correctly, In the Name of God. The film was produced for television, and though I have tried hard to track it down, I have had no success. I can’t remember whether Morocco was the setting or whether just a few scenes were shot there, though I think it was the former, but some of the scenes took place at the annual moussem at Moulay Bouchta.

A moussem is a Moroccan festival, often centered on the annual celebration of a saint. This term saint, in Christian minds, may conjure up a concept that is not quite right. I usually cringe at religious analogies as they can carry over a host of accompanying information from their contexts that is inapplicable or misleading. I suppose it is human to take the unfamiliar, and fit it into a context that gives it sense, but things are not always what they seem. Christian saints act as intermediaries between the faithful and God. Islam, at least in orthodox Sunni Islam, the tradition followed in Morocco, has no place for intermediaries. A Muslim’s connection to God is direct.

Furthermore, saints, in the Western Christian religious context, are canonized, that is to say vetted, by the ultimate religious authorities. Saints in the Moroccan context are largely popular and rural, and gain followings outside of the influence of urban religious authorities. As in most of the Islamic world, it is urbanites in Morocco who control what defines Islam, and they may provide legitimacy to rural saints. Articles of belief are well defined, but there is usually debate and tolerance about the practice of Islam.

The colonial French used an additional term to describe Muslim saints: marabout. This term can also apply to the physical structure where the holy man is buried. The French word may have an associated meaning of sage or wise man.

There is a long-established French publishing house, Editions Marabout, though its symbol is the marabout stork, chosen as a trademark on the model of the Penguin one. If you know your birds, you will know that this is not the elegant bird that nests in Morocco, but a large sub-Saharan predator and scavenger, rather formidable in appearance.

Marabout publishes how-to-do-it and leisure time books in a small square format.

The Arabic root of marabout has the meaning to be tied or to be bound, and is found in the name of Morocco’s modern capital, Rabat. The Berber dynasty, the Almohads, who founded the modern city, called it Ribat al-Fatah. A word for fortress, other derivations from the root appear in family names such as Morabit, and, in Spain and Portugal, Morabito. The meaning in the verb root includes the tethering of horses in a fort, and murabit can mean a soldier or cavalryman. In a more metaphorical context, the word may mean binding in a spiritual sense. Disciples of the saint are tied to their master through beliefs, practices, and devotion.

In North and West Africa, the French term marabout commonly refers to holy personnages, known in their lifetime for their piety, special religious knowledge, and often miracles.

There is another common term associated with Muslim holy men: sufism. Sufism often involves claims to a personal knowledge of God through esoteric practices. In practice, it covers a vast range of activities from simple prayers to enhanced states of conciousness. Usually tolerated, sufism, when taken to extremes, has resulted in conflict with the authorities and even capital punishment for heresy. Some Moroccan saints were sufis, some were not. There is a wide overlap between sufism and sainthood in Morocco.

Saints are addressed as sidi or, if they are chorfa, descendants of the Prophet’s family, moulay, both terms analogous to “my lord,” but the latter, indicating a heritage back to the Prophet Mohammed, and used for the king of Morocco and any descendant of the Prophet, whether a saint or not. That said, the royal pedigree of the Alaouite Dynasty, which has ruled Morocco since the seventeenth century, traditionally includes having a claim to baraka, too.

In Morocco, a saint may be a sufi, or not, but he definitely has a claim to baraka, a holy and spiritual force, that works in this world. People will come to the saint’s tomb, often called a qubba, bringing offerings, and asking for favors from the saint, cures for illnesses, a pregnancy, etc. Baraka is transferable, and may flow from one person to another. A saint with baraka is able, even after death, to share it with followers. Baraka may even be sapped or stolen under certain conditions. Baraka represents Morocco for me, the spiritual and the good, under the surface everywhere.

You can quickly gain an idea of the prevelance of saints by looking at a map of North Africa, where toponyms containing “Sidi” or “Moulay” are scattered all over the map. The home of the French Foreign Legion was Sidi Bel Abbes in Algeria.

Tombs of saints, qubba, show a great variety of appearance, and may not have the visible dome the Arabic word suggests. I have always disliked how Geertz describes them dismissively in Islam Observed, an otherwise wonderful comparison of Islam in Morocco and Indonesia. A saint’s resting place may come in many different sizes and shapes. Some have domes, some have wooden roofs, some have green tiles, the religious color associated with the Prophet, some are caves, and some are not much more than simple graves marked by a cairn or stones.

If the saint has a large following, he may have a lodge, called a zawiya, where adherents to his teachings or way, tariqah, worship together. The lodges are kept up by the descendants of the saint, who receive gifts from visitors as well as offerings during major pilgrimages.

Many lodges are supported by religious trusts, and some are also favored with donations from the government from time to time. Moulay Bouchta is among the latter. My visit to it in September 1969 or 1970 is documented in the photos that follow in this post.

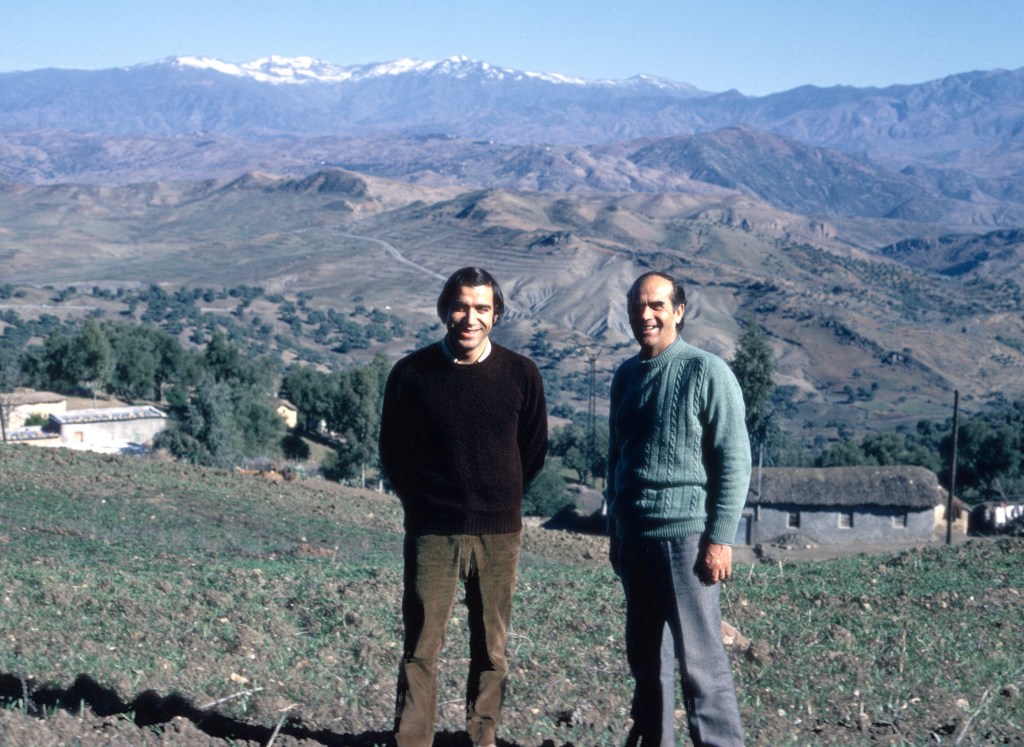

At that time, I worked for the Ministry of Agriculture in Fes and the zawiya of Moulay Bouchta was in the territory of Fes Province. It’s about 45 miles (60 kilometers) north of Fes. Today it is in a more recently created province, Taounate. I often refer to the area north of Fes using the geographical term, pre-Rif, but the area of hills and mountains at the very western end of the Rif is commonly referred to as the Jbala. The route from Fes to Tangier and Tetouan passes through it, and, in the past it was an important connection to Andalusia for the city of Fes.

The moussem at Moulay Bouchta was an annual affair, and locally quite a big event, drawing many local people who celebrate it regularly as well as pilgrims from more distant parts of Morocco.

Visitors pitched tents and camped on the open land around the zawiya and created a cross between a village and a suq (market). Goods and services were sold and traded by merchants and locals, and the main streets of the tent city resembled a rural market, or suq, common in all of Morocco. Visitors to the moussem needed food, services, souvenirs, and, perhaps, offerings. The difference is that the vendors in a suq are usually grouped in a central area, whereas here they lined thoroughfares that cut through the visitors’ tents.

For those unfamiliar with the term, a suq is a market. The term in urban areas means an area where certain goods were sold, and westerners often refer to them as bazaars. In traditional Morocco, suqs were often rural, periodic markets, and bear the name of the day the market is held. Where towns grew up around these periodic markets, they often are named for the day, for example Souq el Khamis (Thursday market). Again, because these markets were so common, there is usually an additional place-name designating location, for example Souq el-Arba’a (Wednesday) du Gharb is a major town in the Gharb region.

Look at an old map of North Africa again, and you will see place-names starting with souq (or zoco, in Spanish) everywhere. Many markets used to be completely rural, but over time most have had small settlements grow up beside them.

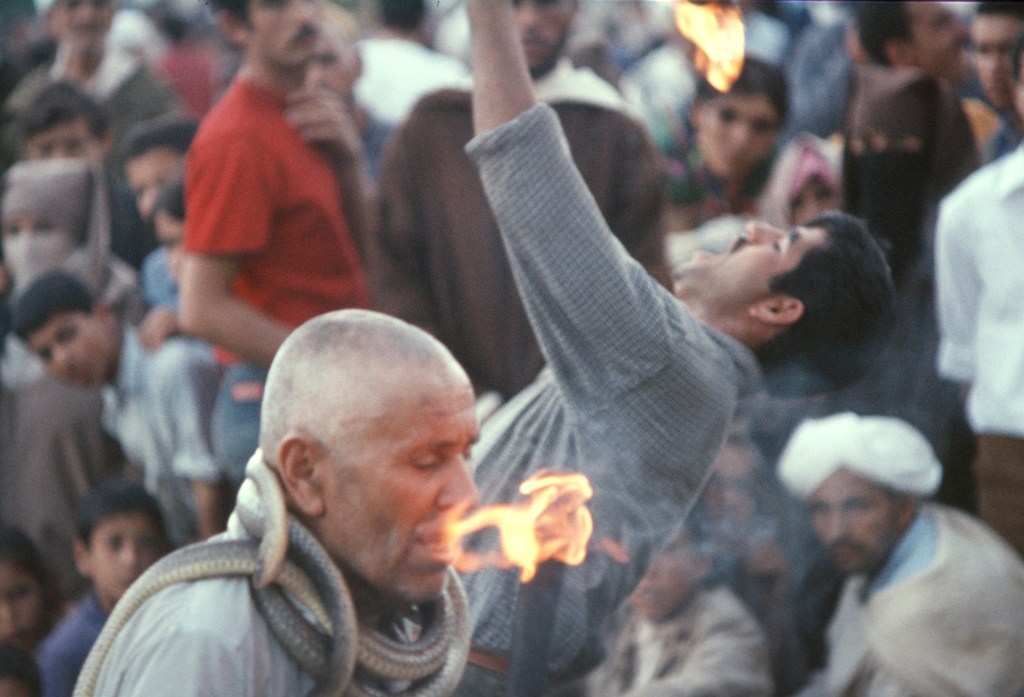

Important moussems were big gatherings, and places where the government liked to show the flag, so to speak. There were usually tents for government officials and local notables, entertainment such as music and dancers, and food. The dancing struck me as incongruous given the religious nature of the spectacle. Women who dance in public are viewed as prostitutes. But the government tents were far from the shrine.

The overall impression was, in my imagination, of a medieval or more modern rural fair, though I cringe at comparing modern Morocco to medieval Europe. The biggest part of the comparison lies in the rural character of the gathering. Think The Mayor of Casterbridge, without the drinking.

I no longer remember how I got there, but since I spent some time in the government tents, I was probably with others from the Ministry. I often worked in the area north of Fes. I have no memory of eating, but I must have been fed. As far as I was concerned, the event was a feast for the eyes.

I do remember that it was a beautiful day and that I spent all of it wandering through the crowds, and taking photos. I seem to have been the only non-Moroccan there, but no one paid much attention to me. I was able to shoot some of the events associated with honoring Moulay Bouchta, as well as the activities of tradesmen and spectators.

Who was Moulay Bouchta? If you know Moroccan Arabic, you will recognize that the name means literally the father of rain. His saintly powers included bringing rains in a time of drought. In a Mediterranean climate such as Morocco’s, rain falls irregularly. In a decade, there may be four years of average rains, but also six others with too little or too much. Drought is a major concern to Moroccan farmers, especially small farmers on marginal plots.

In hilly regions such as the pre-Rif, olives are common since their deep roots allow the trees to survive long, hot and dry summers. Still, the basis of small farmers’ cultures was cereals, and those crops depended on the correct amount of rain at the right time.

Moulay Bouchta was a descendant of Idrissid chorfa, descendants of the first the first Muslim king of Morocco, Idriss I, who was a descendant of the Prophet Mohammed’s family.

Having studied in Marrakech, Moulay Bouchta finished his education at the Qaraouyine University in Fes. A native of the Ouled Saïd tribe from the Chaouia, the plains south of Casablanca, he finally settled among the Fechtala in the vicinity of Amergu, where he died on November 20, 1588.

The moussem used to be celebrated in the spring, after the harvest, but now seems to be in the early autumn. I don’t know why the timing changed. The spring celebration is certainly a more timely harvest festival since the cereal crops are harvested then.

Much of what I know about the Moulay Bouchta comes from a tourism article, written in 1931, by a military man, Paul Oudinot, entitled Moulay Abi Cheta ou Moulay Bouchta. I found it on a blog, A l’ombre de Zalagh. Zalagh is the mountain that overlooks Fes, and the blog site republishes old colonial articles, sometimes with new photos added, on the city of Fes and its hinterland. I strongly recommend it for anyone interested in Moroccan history and the region of Fes.

The foundation of Moulay Bouchta’s zawiya seems to go back to the sixteenth century, when the holy man settled among the Fechtala tribe. Moulay Bouchta and followers were involved in the struggle against the Spanish and Portuguese to take back enclaves on the Moroccan coast and push the Iberian powers out of North Africa.

In modern times Moulay Bouchta is celebrated by hunters and cavalrymen as a moudjahidin. Another claim to fame involves ridding the countryside of the birds that once devoured farmers’ grain. The Heddawah, a local group, assisted the saint in his fight against the birds, so he has looked over them, and became a patron of the modern Heddawah, a religious brotherhood of wanderers, known for smoking kif (marijuana.). Moulay Bouchta is also a saint of musicians, who, according to the saint’s followers, cannot perfect their art without the saint’s baraka.

There are many interesting stories about Moulay Bouchta, who also bears the flattering sobriquet, the Drunk ( مولاي بوشتى الخمار ), not because he drank alcohol, but because he was intoxicated with God.

His remains were once stolen by another tribe, which set up a zawiya in their land, but the Fechtala, after a struggle, were able to return the saint’s remains to their own zawiya. There is to this day, I think, another “little” Moulay Bouchta not far away. The true Moulay Bouchta lies near Amergu. It is a substantial shrine, and he draws visitors widely in Morocco.

That story reminds me of European cases involving the theft of sacred relics by monks of different monasteries, a common practice in medieval Europe. Conques and Vézelay are examples of this in French history.

This was the end of my day. The ceremonies continued into the evening, but I had to return with my co-workers to Fes. The spectacle was over for me.

Truly an impressive and detailed account. These moussem pictures our bound to evoke memories, in those of us touched by the place, of the sounds and scents that so magnified the experience of these events. Sadly the wave of intolerant Islamic fundamentalism that has most recently swept across North Africa has seen the destruction of nearly all the marabout shrines in Tunisia and Algeria. Morocco has taken vigorous steps to stem the this pernicious tide of intolerance, as it threatens the very legitimacy of its cherifian monarchy, and is so foreign to the Berber and Andalusian cultures in what has been called “The Fortunate Kingdom”. Morocco, defined by its Arabic name “Maghreb”, literally “place in the west”, has been protected from Middle Eastern influences by distance, and its formidable eastern frontier of mountain and desert terrain.

LikeLike

Thanks, fascinating as always. I love the cover of the pétanque book, what is that woman thinking about?

I also have a small confession. I especially like looking for the cars in your photos. This time there’s a rather splendid red Simca in the photograph of the western gate!

LikeLike

I do, too. In 1968, remember the old Citroens, not the 1950 ones, but the gangster types of the 1930s and 1940s. The intercity taxis were ether Mercedes or 1950s or very early 1960s American sedans, bought off service men from the big American airbases.

Thanks for your comment. I’ve been going back through your blog, reading old articles that I’ve missed, and I’ve been enjoying them.

LikeLike

This was a really informative post, Dave, with plenty to interest the reader. The fact the one of the tombs (the tomb of Chérif Sidi Moulay Lahcene ) is now in ruins testifies to the historical importance of your work. Your photos add to the details and you have produced another vivid snapshot of your interesting life in North Africa; I enjoyed this one!

LikeLike