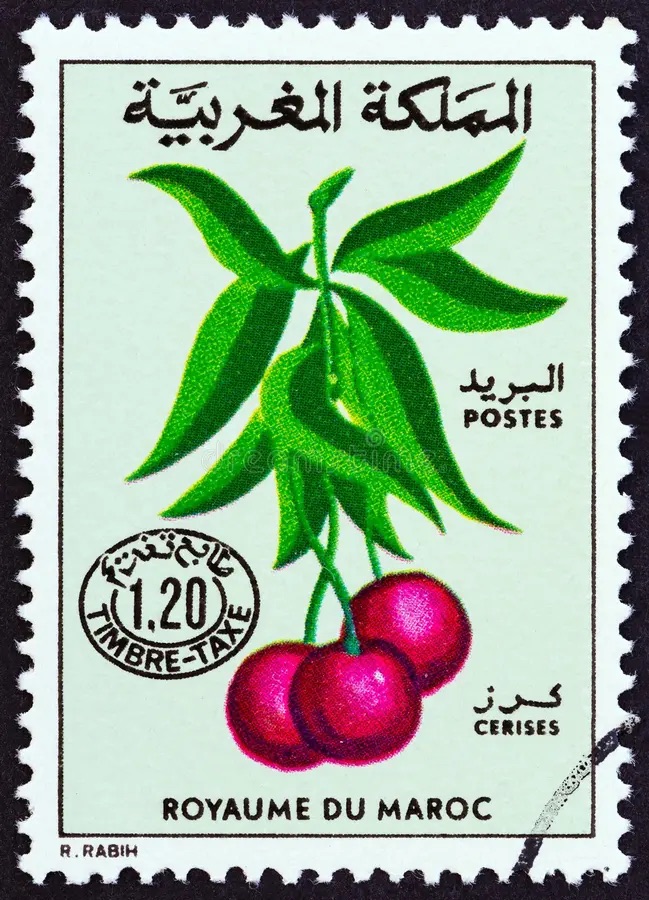

Récemment un lecteur marocain de ce blog, qui m’écrivait de l’Alberta, m’a demandé si j’avais des photos que je pouvais partager de la fête des cerises.

Le Maroc, spectaculaire par sa beauté naturelle, est également un pays de spectacles. Quant à moi, le festival folklorique de Marrakech vient immédiatement à l’esprit, ainsi que les diverses célébrations de saints hommes et de confréries religieuses. Ceci étant dit, il existe au pays de nombreux festivals plus modestes et moins connus. Parmi eux, le festival des cerises de Sefrou, dont le premier date de 1920, est le plus ancien.

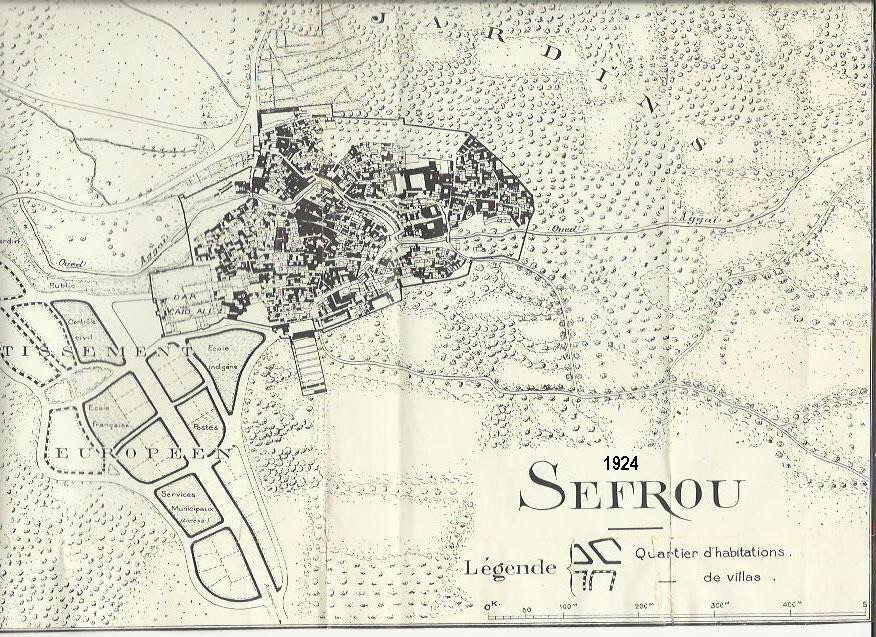

Sefrou, à seulement 28 kilomètres au sud de Fès, possède l’une des fêtes locales les plus connues, la fête des cerises. Cette ancienne ville, très proche de Fès, est traditionnellement le dernier endroit véritablement urbain au sud de Fès, sur une route autrefois connue sous le nom de treq es-sultan, soit la route du roi. Une grande route suit l’ancien itinéraire des caravanes, traversant le Moyen Atlas, descendant dans les plaines de la haute Moulouya, puis remontant pour traverser le Haut Atlas et aboutir à Tafilelt, berceau de la dynastie alaouite, à l’extrême limite du Sahara. Aujourd’hui, les touristes empruntent cette route pour atteindre les impressionnantes dunes de sable d’Erfoud, et les camionneurs transportent leurs cargaisons de produits manufacturés, de dattes et de safran vers et depuis Fès, en bravant les routes glissantes et enneigées des plateaux du Moyen Atlas.

La ville, qui abritait autrefois une très importante communauté juive, est aujourd’hui visitée par de nombreux touristes juifs depuis l’établissement de relations diplomatiques entre le Maroc et Israël. Il existe plusieurs sites Internet consacrés aux Juifs de Sefrou, et la ville elle-même remonte à l’époque de la fondation de Fès, ou peut-être même plus tôt.

Peu de temps après mon installation à Sefrou en 1968, j’ai assisté pour la première fois à la fête des cerises de Sefrou. Gaylord Barr se trouvait déjà à Sefrou, où il travaillait à l’un des centres de travaux agricoles du ministère de l’agriculture, et Jerry Esposito enseignait l’anglais au lycée qui venait d’ouvrir, bien que Jerry ait peut-être déjà terminé son service et quitté le pays en juin. Carolis Deal et John Abel, qui avait initié dans une école primaire le poulailler dont j’ai pris la responsabilité, étaient eux aussi déjà partis.

La proximité de Sefrou avec Fès et la facilité d’accès ont fait du festival des cerises une attraction régionale majeure et, comme des volontaires demeuraient déjà à Sefrou, trouver du logement n’a jamais posé de problème.

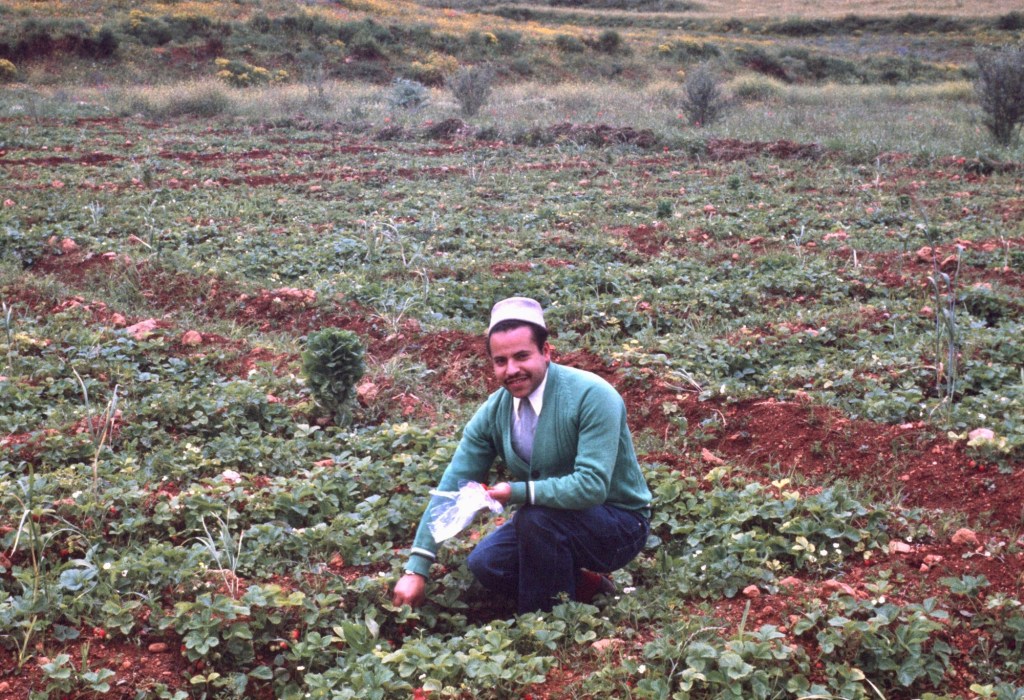

Je ne savais pas grand-chose de cet événement, si ce n’est qu’il mettait en vedette les cerises. Les Marocains appellent les cerises hab el-moulouk, ce qui signifie l’amour des rois, et la variété locale, el-beldi, est réputée pour être particulièrement sucrée et savoureuse. Sefrou occupe une dépression montagneuse à une altitude suffisamment élevée pour que les cerises y prospèrent, mais la ville comptait de nombreux autres fruits et légumes dans les anciens jardins qui l’entouraient. Dans les vergers qui entouraient la ville, poussaient des oranges, des grenades, plusieurs variétés de figues et de nombreux oliviers. Personnellement, j’ai préféré les fraises locales aux cerises.

De nos jours, la population de la ville a connu une augmentation fulgurante, doublant depuis l’époque ou j’y ai vécu, et la zone bâtie s’est étendue bien au-delà des murailles de la vieille ville. Cette croissance a surpris Gaylord Barr qui a fait un arrêt à Séfrou lors de son retour de l’Arabie saoudite en 1997. Dans mon souvenir, les zones extra-muros, à l’exclusion de la ville nouvelle, se limitaient essentiellement aux quartiers de Derb el-Miter, Habouna et Seti Messaouda. Je fais cette digression sur la démographie et l’urbanisation de Sefrou avant l’étalement urbain pour souligner à quel point il était facile de sortir de la médina et, en quelques minutes, de se retrouver dans les jardins qui entouraient la ville. Le vendredi, les femmes se promenaient en groupes, leurs petits enfants à la main, pour pique-niquer dans les vergers, manger des fruits frais, prendre l’air et, bien sûr, bavarder autour d’une tasse de thé. J’ai apprécié la proximité de la campagne et je faisais fréquemment des promenades au village avoisinant de Bhahlil, célèbre pour ses habitations troglodytiques.

On parlait de Sefrou avant l’inondation. Je me demande s’ils parlent aujourd’hui de Sefrou avant l’étalement urbain, l’époque où tout le monde, à l’exception des riches, des puissants et des étrangers, vivait dans la médina et autour d’elle. Les jardins et les vergers de Sefrou caractérisaient la ville à cette époque, et les voyageurs la comparaient parfois à une oasis.

Le terme moussem a été utilisé pour décrire le festival, mais d’après ce que j’ai pu comprendre, la fête des cerises, créée vers 1920, se célébraient plutôt comme une foire agricole au sens européen ou américain du terme. Le mot moussem a souvent le sens d’un pèlerinage religieux sur la tombe d’un saint local, pratique fréquente au Maghreb. Il y avait plusieurs zawias, ou confréries religieuses, à Sefrou, ainsi qu’un marabout et quelques lieux sacrés aux yeux des habitants, mais je n’ai assisté à aucune célébration religieuse régionale de l’importante de celles que l’on trouve à Moulay Bouchta ou à Jbel Alam. Le festival des cerises est apparu comme un événement uniquement séculier dans un pays où la religion imprègne généralement la plupart des cérémonies publiques. La sélection d’une « Miss Cerise » et le défilé de la jeune femme m’ont semblé en contradiction avec les valeurs de l’islam.

Il y avait, bien sûr, les habituels dîners sous tente pour les dignitaires locaux que l’on trouve lors de toute célébration publique marocaine, ainsi que des marchands ambulants qui offraient toute sorte d’articles, de nourriture, de sucreries et de boissons. Les gens circulaient dans la ville nouvelle.

Un jury composé de personnalités locales sélectionne une Miss Cherry, qui défile dans la rue principale de la ville nouvelle à bord d’un char. L’un des chars de cette première année comportait également des danseurs qui se produisaient au fur et à mesure du défilé.

Le défilé comprenait l’exhibition publique d’une femme, ce qui est tout à fait inhabituel dans un pays où les femmes se couvrent en public. La foule qui se pressait le long de la rue principale de la ville nouvelle faisait preuve de curiosité.

.

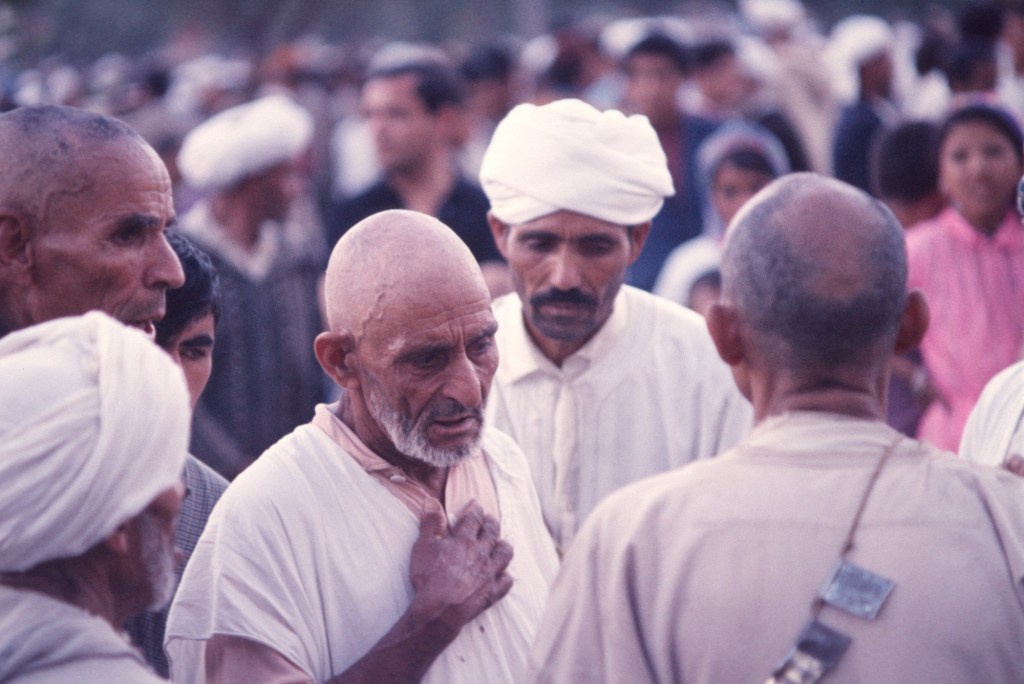

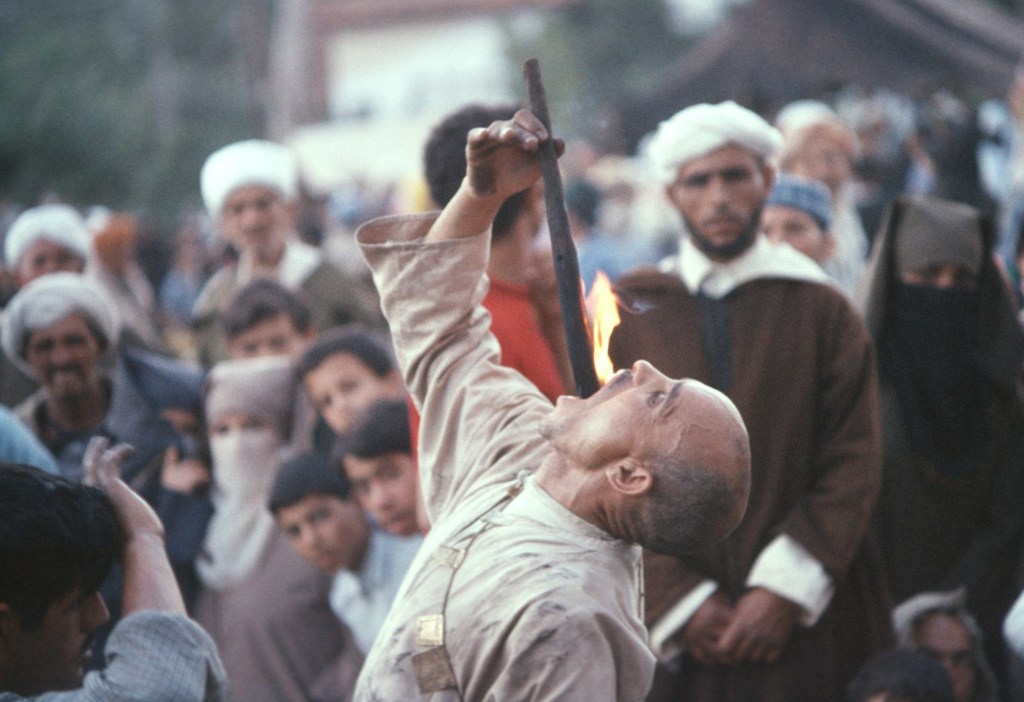

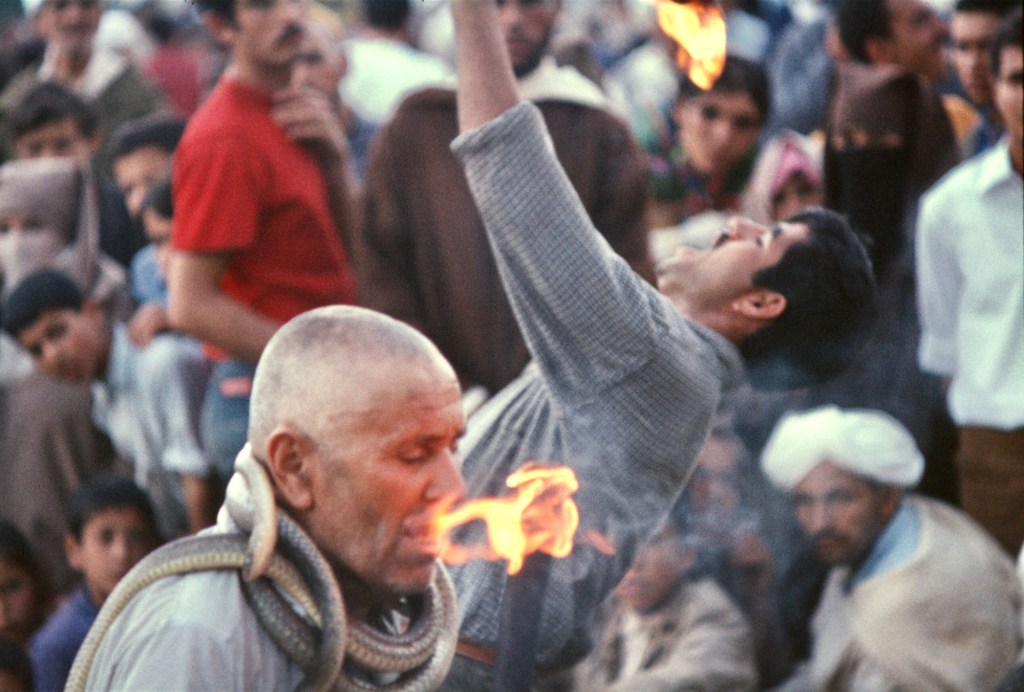

Le festival donnait l’occasion aux confréries religieuses de se réunir et de se livrer à leurs activités particulières, peut-être comme un divertissement pour les spectateurs, mais comme un rituel sérieux pour les participants.

J’ai toujours appelé ceux que j’ai vus Aissawa, ce qui aurait fait d’eux des membres de la confrérie soufie centrée à Meknès. Il existe à Meknès un grand sanctuaire avec un mausolée où repose le maître soufi Ben Aissa, également appelé shaykh el-kamal, le chef parfait. Un important moussem s’y déroule chaque année le jour de la naissance du prophète Mahomet, le Mouloud.

Lors du premier festival des cerises auquel j’ai assisté, un groupe d’Aissawa ou, peut-être, d’Hamadsha, qui mangeaient du feu et manipulaient des serpents mordants, ont dansé jusqu’à l’état de transe. Quelques-unes des photos montrent les visages écarquillés des spectateurs : ces spectacles étaient loin des rituels formels de l’islam de tous les jours !

Traditionnellement le festival durait trois jours, mais je ne me souviens que d’une seule journée. L’année suivante, en 1969, je me trouvais peut-être ailleurs pendant le temps du festival. En 1970, j’y ai de nouveau assisté et cette année-là, il y a eu une fantasia, un spectacle traditionnel de jeux de poudre et d’équitation—le seul auquel j’ai assisté pendant mon séjour au Maroc. Enfin, le seul comportant des chevaux, car à Moulay Bouchta, un cortège d’hommes armé de vieux mousquets s’était rendu sur l’espace devant le sanctuaire et a offert un spectacle impressionnant.

A la fête des cerises, les cavaliers alignaient leurs chevaux sur un terrain plat, les éperonnaient et galopaient le long du terrain en agitant leurs mousquets avant de tirer une salve en l’air.

.

Les photos de ce billet présentent la fête des cerises telle que je l’ai vécue, à la fois en tant que nouvel arrivant dans le pays et en tant que personne ayant vécu à Sefrou pendant quelques années. Les foires d’État et de comté sont courantes aux États-Unis et au Canada, partout où l’agriculture est importante, mais je n’ai jamais visité la foire du comté de Niagara à Lockport, dans l’État de New York, près de l’endroit où j’habite. Les foires, ce n’est vraiment pas mon truc, même si assister à l’exposition nationale canadienne a été un moment fort de mon enfance, parce que j’aimais les manèges et la nourriture.

Le festival des cerises a été très divertissant. En juin, il faisait toujours beau. La ville nouvelle était bondée, les animations étaient intéressantes et des amis de tout le Maroc venaient nous visiter. Ceci étant dit, bien des années plus tard, maintenant que je suis de nouveau chez moi, je ne me rends pas au festival de la pêche à Lewiston NY, à seulement 12 kilomètres de chez nous, ni au festival de l’éperlan de Lewiston, un événement beaucoup plus modeste célébrant le petit poisson savoureux qui remonte la rivière au printemps. Je trouve que les foires sont faites pour les jeunes, les exposants, les vendeurs et les marchands. Toutefois, le festival des cerises est désormais reconnu par l’UNESCO comme faisant partie du patrimoine national du Maroc. Si vous vous trouvez dans le nord du Maroc en juin, je vous encourage à y participer. Au minimum, vous aurez le plaisir de voir des foules de Marocains s’amuser. À l’époque où je restais au Maroc, la vie était difficile pour beaucoup et les fêtes nationales ou locales s’avéraient des occasions de célébrer avec des amis et avec la famille. Je m’imagine qu’à cet égard, rien n’a changé du tout.